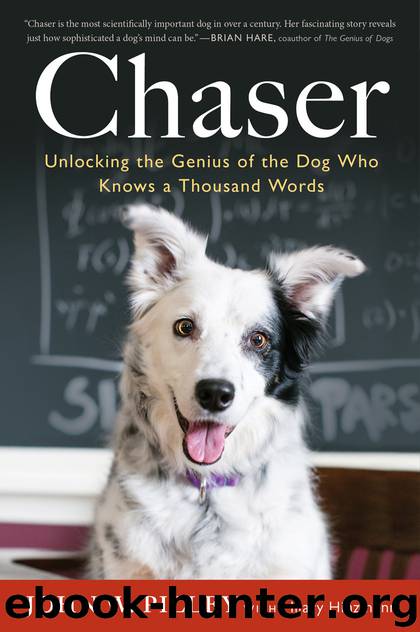

Chaser_Unlocking the Genius of the Dog Who Knows a Thousand Words by John W. Pilley & Hilary Hinzmann

Author:John W. Pilley & Hilary Hinzmann [Pilley, John W. & Hinzmann, Hilary]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

Published: 2013-10-29T00:00:00+00:00

12

Getting Published

BY THE TIME Chaser turned three in the spring of 2007, she knew more than a thousand objects by their proper noun names. There were 800 stuffed animals, 116 balls, 26 Frisbees, and 100-plus plastic and rubber items. I began writing a paper that would share the impressive results of her learning. I hadn’t written a peer-reviewed paper in a long time, but I knew the form well. And I thought I had an excellent recent model in the Rico paper, which was distinctive not only for its content but also for its fairly conversational style, though I intended to provide a more thorough explanation of my training and testing procedures.

I included the full spectrum of language learning I observed in Chaser, even if I didn’t have extensive data on some aspects of it. I believed that the remarkable nature of the findings would justify publication in journal editors’ eyes. I entitled the paper “Can a Dog Learn Nouns, Verbs, Adverbs, and Prepositions?”

My hope was that Science, the world’s most prestigious scientific journal along with Britain’s Nature, would publish the paper as a sequel of sorts to the Kaminski paper on Rico. And I hoped they’d ask Paul Bloom to contribute another “Perspective,” in which he would acknowledge that Chaser’s learning met all the basic criteria for word learning. Toward the end of the summer I told Alliston Reid that I was going to send the paper to Science.

With a smile Alliston said, “They only give you one shot there, John.”

“I know,” I said. “But they published the Rico paper and I’ve gotta think this is a pretty good shot, given how much Chaser has learned and how she’s met Bloom’s and Markman and Abelev’s major criteria for referential understanding. Here’s hoping, anyhow.”

A few days after that, with my eyes blurry from reading and rereading for typos and grammatical errors, I sent the paper to Science. Several weeks later an editor at Science briefly e-mailed me to say that upon review they were rejecting the paper. There was little detail as to what might have been said about the paper during the review process or what its specific flaws might be.

I was stunned.

Rereading my paper, I confirmed that my experimental procedures in testing Chaser’s understanding of proper noun words and her ability to learn by exclusion were identical to those in the Rico study. In addition I had sharpened the paradigm for testing Chaser’s exclusion learning by establishing that she had no baseline preference for novel objects. Likewise, I had described rigorous procedures for teaching and testing the learning of common nouns.

But I had to admit that some critical details of my studies were missing. Unfortunately I had not presented the usual tables and figures to display my findings but had only described them in words and a few key numbers. I also recognized that much of the paper was too informal and did not say enough about how Chaser attained her language learning and how I tested it. So I optimistically set about rewriting the paper.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind by Yuval Noah Harari(14392)

The Tidewater Tales by John Barth(12662)

Mastermind: How to Think Like Sherlock Holmes by Maria Konnikova(7351)

The Thirst by Nesbo Jo(6946)

Do No Harm Stories of Life, Death and Brain Surgery by Henry Marsh(6944)

Why We Sleep: Unlocking the Power of Sleep and Dreams by Matthew Walker(6727)

Life 3.0: Being Human in the Age of Artificial Intelligence by Tegmark Max(5559)

Sapiens by Yuval Noah Harari(5374)

The Body: A Guide for Occupants by Bill Bryson(5100)

The Longevity Diet by Valter Longo(5067)

The Rules Do Not Apply by Ariel Levy(4972)

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot(4592)

Animal Frequency by Melissa Alvarez(4474)

Why We Sleep by Matthew Walker(4449)

The Hacking of the American Mind by Robert H. Lustig(4386)

Yoga Anatomy by Kaminoff Leslie(4367)

All Creatures Great and Small by James Herriot(4326)

Double Down (Diary of a Wimpy Kid Book 11) by Jeff Kinney(4275)

Embedded Programming with Modern C++ Cookbook by Igor Viarheichyk(4182)